Beyond human-centred AI

“We should all ask, what would our planet look like in Indigenous hands?”

(Source: National Geographic Explorer Keolu Fox says the key to harnessing the technology of tomorrow is centring traditions of the past).

What is Indigenous AI, and Why does it matter for AI overall….

This post will explore the emergent space of Indigenous AI. It is currently researched in not-for-profit initiatives which aim to connect marginalised cultures, their languages and ideas.

Indigenous AI presents the possibilities for “an alternative reality” to the technology sectors’ ultra-capitalist model. Extractive capitalism is not an inevitability in AI, particularly if we can support new models in which “Indigenous perspectives on relationships to land, sea, sky, and cosmos are the guiding force.”

In my view, a lot can be gained from the story of this space! Many universal principles for AI can be gleaned from this amazing and ongoing work.

Thanks once more to my research & thought partner Ve Dewey for making this happen.

This article will talk about Indigenous AI from the 3 following perspectives

Diversifying “AI” - Bringing in wisdom from outside the predominantly English language and secular AI landscape. Embracing Indigenous cultures’ symbiotic existence with the natural world

Informing decentralised AI - Highlighting design possibilities through principles of decentralisation via collective wisdom

Protecting and documenting - The usefulness of AI for the preservation of endangered languages and cultures

But as an introduction, what does it mean to be indigenous?

Indigenous knowledge, also known as traditional knowledge, includes know-how, practices, skills and innovations. It can be found in a wide variety of contexts, such as agricultural, scientific, technical, ecological and medicinal fields, as well as biodiversity-related knowledge. It is intertwined with cultural and social practice and Indigenous language.

It is estimated that more than 370 million indigenous people live in 70 countries worldwide. Because they practice unique traditions, they retain social, cultural, economic, and political characteristics distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live.

They are spread across the world from the Arctic to the South Pacific. They are the descendants of those who inhabited a country or a geographical region at the time when people of different cultures or ethnic origins arrived. The new arrivals later became dominant through conquest, occupation, settlement or other means (source: United Nations).

1. Diversifying “AI” data and perspective

Diversity in AI is impacted by 1. data and 2. by training, which is influenced by biases.

The Indigenous AI community

The Indigenous AI narrative has received much attention in the last few years. This is great, as the conversation is now proliferating.

From the outside, the Indigenous AI community (and to be clear, I am writing this piece as an outsider!) seems quite interconnected / closely knitted. It seems that there are a few more prominent voices, and more partners and support is needed for this to be a meaningful mainstream practice in AI.

A Human Rights-Respecting AI

A very small group of experts is considering the Indigenous values of co-creation, creating interest in future possibilities. As Jason Edward Louis from Concordia University says, “The consequences and impacts of these new technologies on human beings and Mother Earth are unknown.”

Not dissimilar from physical disability to neurodiversity or age, it is a fact that Indigenous groups are often excluded from inclusive design practices, and AI is no different.

But with AI, this issue feels different.

“This is arguably the first major technological revolution in the West where Indigenous Peoples have the capacity to fully participate in its shaping,” says Jason Edward Lewis, who is a professor of computation arts at Concordia University as well as the University Research Chair in Computational Media and the Indigenous Future Imaginary.

Per Stanford’s James Landay’s Human-Centered AI Lab, this goes “well beyond the familiar extremes of utopian techno-solutionist or techno-apocalyptic thinking to consider Indigenous epistemologies and new models for AI.”

This feeling is echoed in the Indigenous community, “We have an opportunity here to affect the trajectory…We don't have an AI ethics problem, we have an AI epistemology problem,” Lewis says.

How can Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies contribute to the global conversation regarding society and AI? How do we broaden discussions regarding the role of technology in society beyond the largely culturally homogeneous research labs and Silicon Valley startup culture? How do we imagine a future with AI that contributes to the flourishing of all humans and non-humans?

The Position Paper on Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence was published in the Spring of 2020. It involved diverse Indigenous communities from Aotearoa, Australia, North America, and the Pacific. This position paper offered a multi-layered discussion on new conceptual and practical approaches to building the next generation of A.I. systems.

In 2023, a comprehensive report released by UNESCO argued that for AI to truly respect human rights, it must incorporate the perspectives of Indigenous communities in Latin America, the Caribbean, and beyond.

The paper, titled "Inteligencia artificial centrada en los pueblos indígenas: perspectivas desde América Latina y el Caribe", authored by Cristina Martinez and Luz Elena Gonzalez, linked its arguments to the broader UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, by highlighting the urgency of developing a framework of shared responsibility among different actors for the collective public interest. See the summary in this awesome post by Enzo Maria Le Fevre Cervini, Head of Sector at the European Commission.

The politics of Indigenous AI

“Data is the last frontier of colonisation,” Keoni Mahelona, founder of Te Hiku Media. (Source: AI Colonialism in MIT Technology Review).

Indigenous is already a loaded term. AI systems exclude most indigenous peoples’ values and belief systems.

Artificial intelligence is creating a new colonial world order. Within this, “Indigenous epistemologies (or theories of knowledge) provide frameworks for understanding how technology can be developed in ways that integrate it into existing ways of life, support the flourishing of future generations, and are optimized for abundance rather than scarcity.”(MIT).

AI is known to be linear in its cultural references, which we have already covered in-depth in previous posts. But there is a newness in the discourse around AI’s exclusion of Indigenous voices in colonial history repeating itself.

In investigating AI Colonialism an MIT technology review series investigates how AI is enriching a powerful few by disposing of communities that have been dispossessed before. LINK to the SERIES

With enough linguistic data, large language models (LLM) could be used to document the world’s threatened languages. By bringing these languages into the digital realm, LLMs could also encourage more people to learn and use them in everyday life.

This has been largely welcomed by the AI sector.

It is a safe way for technology companies to consider diversity in AI, as it is about small and unfortunately marginalised communities, cultures and belief systems.

Unlike the more politically loaded Mandarin, Hindi or Arabic, conserving a language with 1000 speakers has a wonderful feel-good and non-threatening element to it. As a result, it circumvents the more difficult conversations about mainstream AI attempting to integrate other bigger cultures, such as China, or religions, such as Islam.

In engaging with indigenous cultures, big tech benefits from policy or government relationships in countries with large indigenous populations.

IBM’s initiative with researchers at the University of São Paulo are working with Indigenous people in Brazil to develop AI-powered writing tools to strengthen and promote languages at severe risk of decline. Or Meta publicising how its auto translate tools now extend to Dari, Samoan and Tswana.

This is not good enough by itself. As a great editorial in Nature Magazine pointed out, machine-learning models are “only as good as the data that they are fed” — created by humans. The companies behind these platforms need to engage with the communities they aim to serve.

What about the consent of communities?

We’re used to hearing about the post-human, but in the design sector, we are well into the post-natural—and not everyone is on board. Take the example of synthetic biology, a field which is increasingly using AI to supercharge outcomes in material design.

There are various examples of where so-called new technologies relating to the usage of natural materials have been the domain of indigenous communities for years prior. For example, Indigenous communities in Canada and the United States were prototyping their own myco-textiles a century before Stella McCartney debuted a line of fungal leather handbags.

This is unchartered territory in terms of ethical frameworks.

“These genetic resources, in which traditional knowledge is also linked, are used without the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous peoples,” María Yolanda Teran, a Kichwa academic and Indigenous representative to the United Nations, argued last year. “The consequences and impacts of these new technologies on human beings and Mother Earth are unknown.”

A series of co-created artworks were developed between the digital artist Refik Anadol and the Brazilian Indigenous Yawanawa community. This collaboration will expand into a new platform to facilitate the preservation of indigenous languages from around the world.

In this current collaboration, Anadol had the support of the Yawanawa elders; Chief Nixiwaka Yawanawá said, “This partnership that we are building with Refik is directly for our communities. It strengthens our village, it strengthens our culture, it strengthens our spirituality, it gives us strength to defend, to protect our forest”.

A still from the Winds of Yawanawa series, revealing Anadol’s digital painting treatment of traditional Yawanawá art, 2023Image: © Impact One

Anadol said of the project, “We need collective wisdom. And if you think about collective wisdom, you will need ancestral wisdom. At some level, it’s more educational and inspiring—hearing the Yawanawá’s voices and how we are evolving and bringing their perspective to the dialogue is the most fundamental part of the project”.

2. Informing decentralised AI

Presenting possibilities for AI development through indigenous values.

As decentralised options for AI emerge, learning for AI based on Indigenous community or pod-led approaches can be very instructive.

In Making Kin with the Machines, a seminal essay published by MIT Press six years ago, researchers Jason Edward Lewis, Noelani Arista, Archer Pechawis, and Suzanne Kite used Indigenous epistemology to project a future for human, machine, and non-human co-existence.

Man is neither height nor centre of creation. This belief is core to many Indigenous epistemologies. Indigenous communities worldwide have retained the languages and protocols that enable us to engage in dialogue with our non-human kin, creating mutually intelligible discourses across differences in material, vibrancy, and genealogy.

“The current trajectory of AI development prioritises Western ways of thinking about humans and our world.” Therefore, users are served for efficiency and personal well-being rather than broader aspects of human existence such as “trust, care and community.”

How do we as Indigenous people reconcile the fully embodied experience of being on the land with the generally disembodied experience of virtual spaces? How do we come to understand this new territory, knit it into our existing understanding of our lives lived in real space, and claim it as our own?

More than human intelligence

In an article last year in Noema Magazine, the futurist and designer - Anab Jain wrote “Between the void and the waste, where do regenerative and just futures fit? How can we bridge the fault lines between humans and nature, right and wrong, them and us? How can we forge cooperative, plural, interconnected ecologies of actions?

Source: Anab Jain on OnDesign podcast, with Justyna Green. Listen now on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

At a personal level Anab connects back to the myths of childhood - stories on magical creatures, ghosts, talking trees, humming fairies from the planes of Gujarat, where she grew up in forests and nature. “There is the potential to knit stories of care, justice, collaboration, love and tolerance that, like myth, can endure and enact ecological relationality.”

Stanford’s Human-Centered AI Conference in 2023 on Creativity and AI hosted an entire session on indigenous knowledge. Embracing a multiplicity of creation narratives, pushing far outside the aggressively secular frameworks in Silicon Valley. And connecting possibilities of AI and explorations of intelligence through Myths, magic and outcomes in speculative design.

Considering the SACRED, the VULNERABLE, the EARTH & other SPECIES….

The necessity of a symbiotic approach to living within the natural world is particularly prevalent today, as environmental concerns reach all-time highs and technology's rapid development offers potential, mappable solutions.

Writers and artists like James Bridle have interrogated this for some time, exploring possibilities for where machine intelligence can connect with the more than human of other species and more remote cultures.

Abundant intelligence collective

Abundant Intelligence, a multi-year international collaboration between stakeholders from Canada and Aoetera, is a $22 million project that explores how to conceptualise and design Artificial Intelligence based on Indigenous Knowledge systems. C o-principal investigator is linguist Hēmi Whaanga of Te Pūtahi-a-Toi, the School of Māori Knowledge, at Massey University in New Zealand

“We want to expand how we define AI while we build it. The plan is to explore a more extensive spectrum of intelligent human and non-human behaviours that we use to make sense of the world.”

Source: Abundant Intelligence; Creativity in the Age of AI: AI, Art & the Seneca Creation Story, Jason Edward Lewis: Co-director, Indigenous Futures Research Centre and Professor of Design and Computation Arts, Concordia University

3. Protecting and documenting - The usefulness of AI for the preservation of endangered languages and cultures

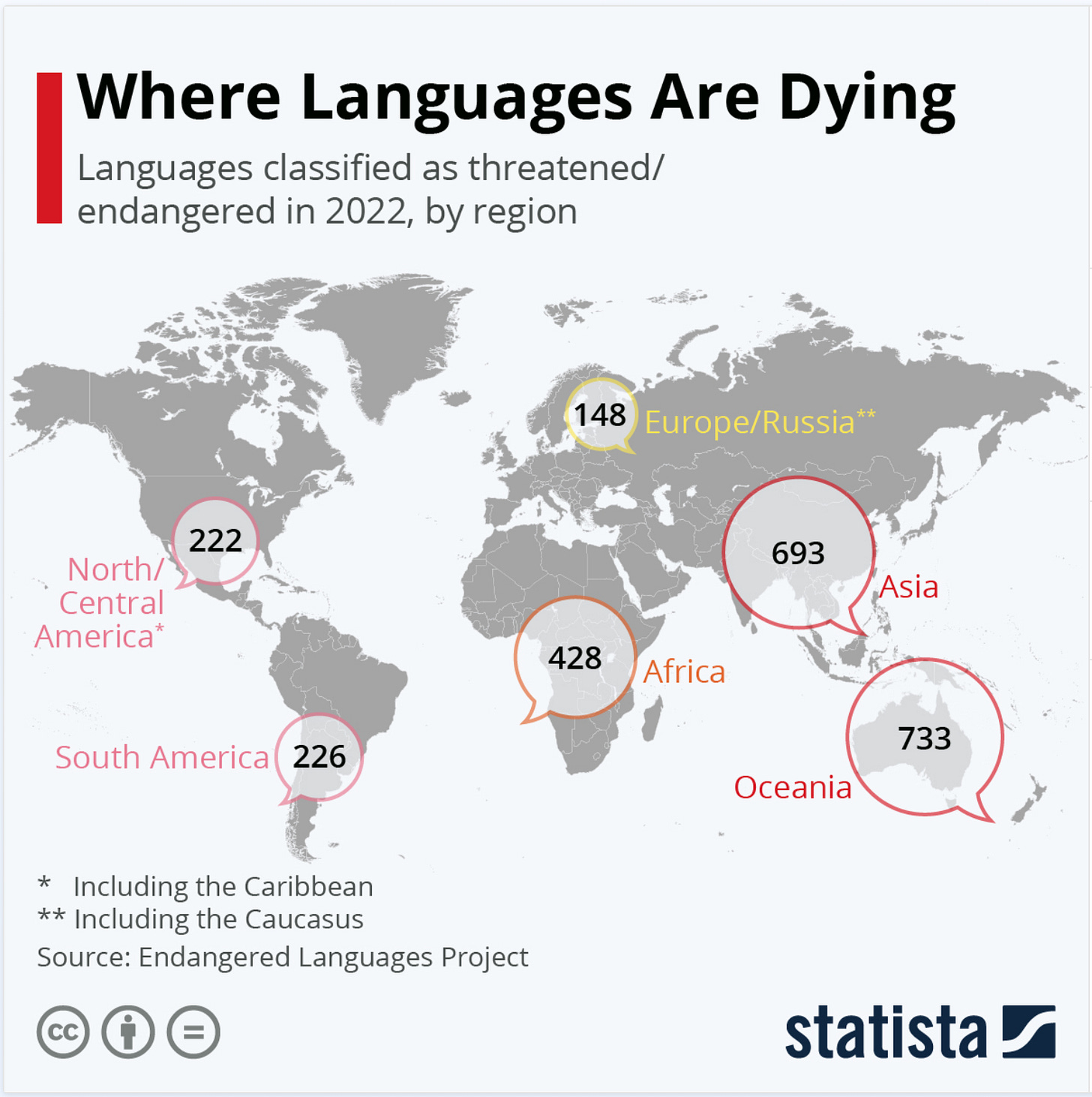

Most of the world’s spoken and written languages are endangered. According to the United Nations, 96% of the world’s approximately 6,700 languages are spoken by only 3% of the world’s population. Amazingly, indigenous peoples make up less than 6% of the global population; they speak more than 4,000 of the world’s languages.

However, if proper preservation is not planned, indigenous languages could become endangered or extinct. By the end of this century, 3,000 indigenous languages could completely disappear.

Source: Visual Capitalist Creator Program

Planetary entanglements

There is also a direct link between disappearing habitats and the loss of languages. One in four of the world's 7,000 spoken tongues is now at risk of falling silent forever as the threat to cultural biodiversity grows.

According to a piece in the Guardian from a decade ago, linguistic diversity is declining as fast as biodiversity – about 30% since 1970. For example, places such as Papua New Guinea have around 1,000 languages, but as the politics change and deforestation accelerates, the natural barriers that once protected them are being eroded or broken.

There is a relationship between AI and Endangered Languages

The internet and AI reinforce the use of English and other dominant languages. There is a lot of online literature on how AI can help / hinder diversity in language preservation.

AI models can convert spoken language into written text, making it easier to document and analyse, and NLP algorithms can gather and organize linguistic data from various sources, including audio recordings, texts, and videos.

Shakhnoza Sharofova, a student of the Uzbekistan State University of World Languages wrote The Impact of AI on Endangered Languages: Can Technology Save or Kill? in 2023. Sharofova argues that, on the one hand, the possibilities offered by AI have significantly enhanced language preservation efforts by providing tools for documentation, analysis, and revitalisation.

On the other hand, there are ethical concerns about incorporating AI in language preservation, which “introduces a complex terrain marked by concerns of cultural appropriation, representation biases, and the exacerbation of existing digital divides. “

What are some examples?

There are many initiatives around the world now using AI to preserve endangered languages, from the Amazon to the Southern Pacific and the hill tribes of Eastern India. The Endangered Languages Project, supported by Google, uses AI to collect and digitize audio recordings of endangered languages.

Te Hiku Media is developing automatic speech recognition (ASR) models for te reo, a Polynesian language.

A recently announced partnership between Camb.AI, and Seeing Red Media, an Indigenous-owned media company based on Six Nations of the Grand River, aims to revolutionise the preservation of and strengthen Indigenous languages through advanced AI technology by leveraging Cam.ai’s text-to-speech technology to develop the first-ever Native Indigenous language and speech model. Similar projects are underway by Native Hawaiians and the Mohawk people in southeastern Canada.

Next post

This was a lot, I know! So will give you a little breath, but as always any feedback is welcome. The next post will be on the hierarchies and nuances of power in AI as a sector.